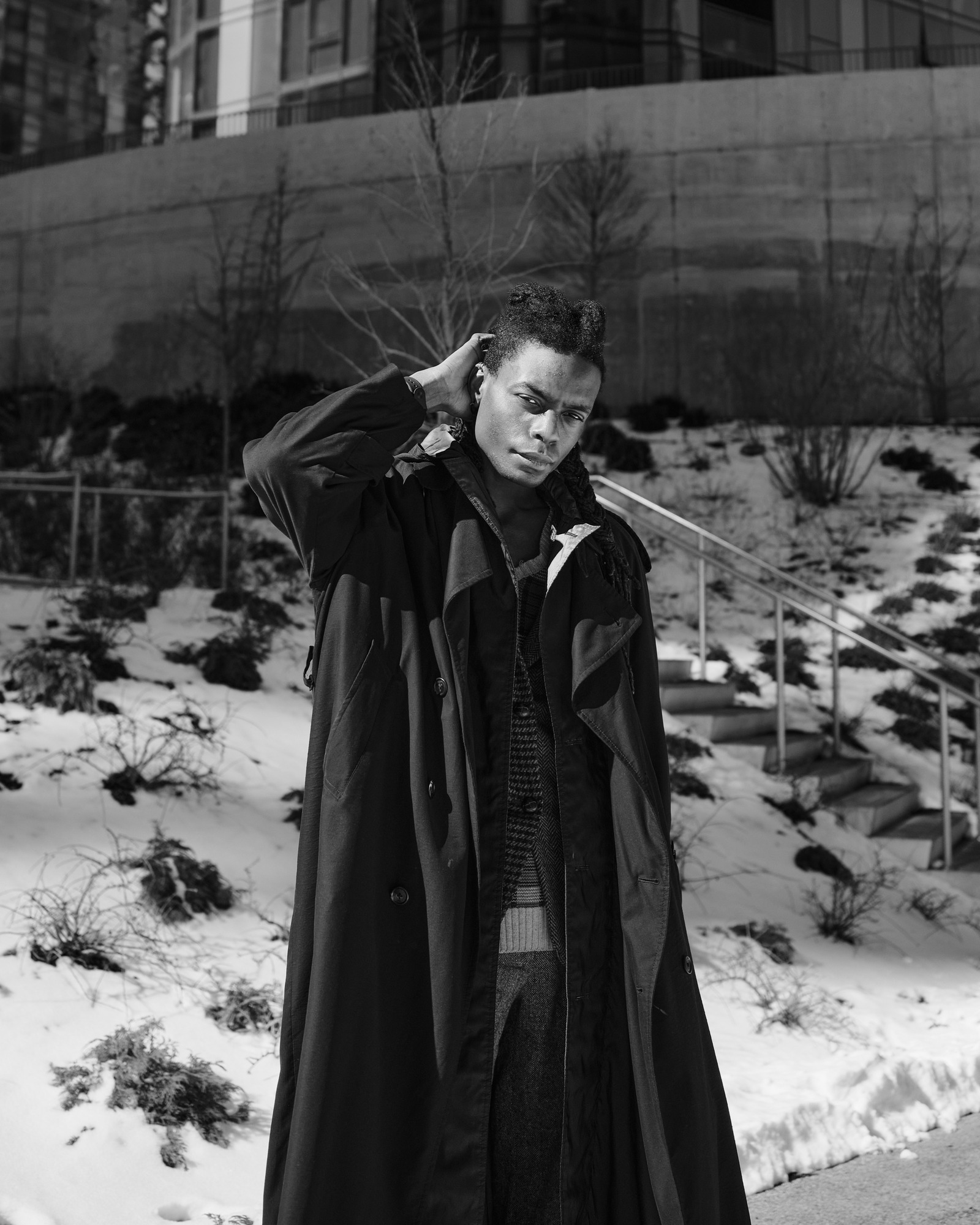

A review of the Fujifilm X-Pro3, the quirkiest camera Fujifilm has ever made

“It’s not a perfect camera, but it’s perfect for me.”

That was how I’d describe Fujifilm’s X-Pro3 when asked; and surprisingly, I was asked a lot. This is a camera that catches your eye. It stands out. And it makes some pretty good images, too.

When Fujifilm announced the camera in October 2019, it immediately became a topic of conversation. No directional pad, no in-body image stabilization, and no flippy screen? What was Fujifilm thinking?? Charitably, some called it “quirky.”

But it always made sense to me. Fujifilm wasn’t making a camera for everyone. They were making a camera for me (thanks, guys!).

The promise was simple: Fujifilm took their most cutting-edge image processing chain and put it in a thoughtfully-designed body, meant not only to emulate the look of a retro camera, but to remove as much as possible between photographer and subject, making image-making second nature.

And it did, for me. I bought an X-Pro3 shortly after launch, and put it through its paces for over five years, before finally moving on in 2025.

I’m not going to say I made more photographs with the X-Pro3 than anyone else, but it was my daily companion for over two thousand days. I captured thousands upon thousands of frames, bought, used, and sold nearly every lens they made for the system, and kept it close to my heart from everything from international adventures to neighborhood coffee runs.

Before the X-Pro3, I thought a camera was a simple tool, something designed by committee to satisfy the largest customer base possible. The X-Pro3 taught me a camera itself could be beautiful, a piece of gear could be opinionated, and an artist's tools could make them a better photographer.

What made it such a special camera, and why did I decide to move on from it? All that and more below.

All images made with the Fujifilm X-Pro3

Breaking the Mold

The Fujifilm X-Pro3 is a rangefinder-style camera—and as I’ll discuss later, that “style” is quite the key term. It’s one of Fujifilm’s flagship cameras in their APS-C “X Series,” alongside the more traditionally-styled (read: SLR-shaped) X-T line, taking the most advanced technology Fujifilm had produced at the time and putting it in a camera body that looks like it came from a vintage shop.

The X-Pro3 made me a better photographer, if by how much it compelled me to use it as much as anything else.

This alone is not that unique of a concept. Indeed, Fujifilm more or less created and then innovated on this segment of the market back in 2011 when it released the X100. Even the aforementioned X-T line has quite the retro look, with dedicated dials for shutter speed, ISO, and exposure compensation—something that had become nearly extinct through years of Canon and Nikon dominance.

But the X-Pro line takes this a step further. Rather than the fixed lens of the X100 cameras, the X-Pro line is a fully-featured, interchangeable lens system that managed to offer the exact same image quality and lenses as the X-T line while completely changing the shooting experience.

The Shooting Experience

And what an experience it is. The X-Pro3 is a beautiful camera in my opinion, made in Japan out of titanium, giving the camera an extremely premium, weighty feel. The first press photos of it sparked something in me like no other camera had before, and once I had it in my hands, I rarely wanted to put it down. Like all great tools, it’s one that makes you want to use it. Beautiful to hold, it was something that once I put it on my desk or on a table at a coffee shop, it called out to me to pick it up and use it.

Through the dials on the top plate, photography’s most essential controls of aperture, shutter speed, and ISO are always within reach. While Canon and Nikon had relegated nearly everything to endless menus, Fujifilm broke through those walls, not only asking why, but answering with a new paradigm of their own.

It's hard to overstate how groundbreaking this felt to me. I had shot film before, but to see everything front-and-center like this completely changed my relationship to image-making. Suddenly, I saw the connection between the points on the exposure triangle, and felt like I could make the images I had intended to.

There’s no PSAM dial here for selecting something like aperture-priority mode—there’s no need. Instead, simply set the aperture to the value you want, and then set the ISO and shutter speed to auto on the dials. It’s so simple, so intuitive, that it makes nearly every other camera control system look like a step back.

Once you’re through initial setup, there’s very little you need to access the menu for. I had gotten mine so tuned in to how I wanted to use it, that on the rare occasion I’d go into the menu, I’d often find some setting I’d forgotten even existed.

But while the X-T line offers versatility, jack-of-all-trades-ness to those that choose to use it, the X-Pro3 is a specific type of camera for a specific type of photographer. This is not a camera meant to photograph herons snatching fish from a lake, or an F1 race, despite the same guts as the X-T3. It’s a camera whose ergonomics suggest a way to use it.

The Screen & Viewfinder

Take, for example, the screen. This is without a doubt the defining design element of the X-Pro3. The “hidden” LCD screen must be folded down from the back for use—intentionally awkward, designed only for reviewing images or the rare time you’d need to dip into a menu. This is not a camera for someone who uses live view more than once in a blue moon.

Instead, once the screen is in its default, closed state, you get a small square window, evocative of the slots on the back of film cameras for placing a reminder of what filmstock you have loaded. And that’s exactly how I used it. I set up a custom profile for each of the film simulations I wanted to use, and once I set out for the day, I’d press the button I’d have mapped to the custom settings, and looking at this little screen, would flick through my presets as if picking my film for the day.

Even the optical viewfinder, the other marquee feature, seems to subtly suggest a use to you. Unlike the dual-magnification X-Pro2, the X-Pro3’s viewfinder offers only one magnification, which in practical terms means it’s most useful for 23mm and 35mm lenses—as I’ll discuss later, lenses squarely in the domain of the street photographer.

But a camera is only half of a camera system. In fact, the other half might be even more important.

The Lenses

Luckily, Fujifilm’s lenses are incredible. This is an under-appreciated aspect of what Fujifilm brings to the table: their superb optics. I shot Canon for years before I switched to Fujifilm, and I never felt inspired by the rendering of Canon glass like I often did for Fujifilm.

Over the years, I bought and sold tons of Fujifilm lenses, and like to joke that I owned nearly all of Fujifilm’s prime lenses at one point or another.

Flat out: the Fujifilm lenses are INCREDIBLE. I felt a particular fondness for the 35mm f/1.4, which rarely left my camera in the last year I owned it, and the 23mm f/2, which I felt had rendering that punched way above its weight class—something about images from this lens always gave me that “3D pop” feeling. (If you get any lens in the Fujifilm system, make it one of these two!)

Even beyond the exceptional rendering is the versatility the Fujifilm system offers. There are cheaper lenses, and premium versions. There are compact lenses, and bigger ones for unparalleled performance. Zooms to primes, macro to extreme telephoto, there is probably a Fujifilm lens that meets your needs.

Film Simulations

Fujifilm’s other main advantage is in their color science. Before Fujifilm, in-camera profiles were seen as a joke. I’ve never seen a Canon photographer switch from “Neutral” to “Vivid.” Perhaps because of the influence of Instagram, or maybe just because of the quality of the filters Fujifilm produced, they mainstreamed the concept, and similar settings can now be found in a range of cameras.

Fujifilm’s take on in-camera profiles is called “film simulations,” and focuses on emulating film, often specific stocks Fujifilm produced, or sometimes an amalgamation of different films, or something inspired by the past. These profiles are applied directly to your JPG, and contained in the metadata of the RAW (though you can make any change you like to RAW images, even changing the film simulation used).

Suddenly, it wasn’t a joke to shoot JPG. And some photographers took it a step further, with entire communities popping up around what people started calling “Film Simulation Recipes,” which suggested alterations to editable properties like white balance and shadow and highlights to achieve even more specific looks.

For my part, I was never quite that involved. I found some simulations and matching settings that fit my style of photography early on, and rarely differed from those six or so profiles. I mapped the custom user setting selection to one of the most accessible buttons on the back, and when I’d head out for the day, I’d select my look—just like selecting a film stock for a day’s shoot—all displayed on Fujifilm’s e-ink subdisplay, always visible on the back of the camera.

Instead, I wanted to focus on finding moments, searching for light. I wanted to be absorbed in the scene around me, as perhaps the camera is designed to facilitate.

Street Photography

The X-Pro3 is a camera for shooting street photography. Its minimal, stripped-down ergonomics cuts through the noise of this era in cameras, offering a shooting experience whose only close competitor was Leica. That’s not to say all the work I made with it is in the realm of street photography—I shot professional work as well, from portraits, headshots, editorial, and commercial—but I don’t think it’s a stretch to say street photography is what the X-Pro3 is designed for.

Street photography is (fraught definition incoming) about capturing candid moments in an urban environment. What about the X-Pro3 makes it such a natural fit for street photography?

The X-Pro3 offers an extremely minimal, pure shooting experience. Like I said earlier, all the most important controls are right at hand, so there’s no need to mess around with menus or ways to forget what mode you’re in. If you want to know what aperture you’re at, you can just look down. This efficiency is highly valued in street photography, where excess can mean missed shots.

Muscle Memory

Most of my interactions with using the X-Pro3 became like selecting my film simulation for the day. Almost every function on the X-Pro3 can be remapped, so you can change the use of nearly every button available. This makes it especially so you never have to dive into a menu; if you’re someone who wants to frequently swap between eye-AF and regular AF, you can make a button for it (or almost any other function).

Over time, this becomes part of your muscle memory; operating the camera becomes second nature. I know what function I need in a moment, and I remember which button I assigned that to. It’s like touch-typing. That closing of the gap between thought and action, between intent and photograph is like magic. Before the X-Pro3, I didn’t know a camera could get out of my way like that.

It’s an extremely un-fiddly camera. That brings me back to shooting film more than anything; the removal of excess, the limitation of controls heightens the impact of what’s available, what’s essential.

My process tended to be as such: I’d gotten most of my settings dialed in from the very beginning, including a number of film simulation profiles. Based on my mood, lighting conditions, and intent, I’d usually pick a profile at the start of a photowalk, along with adjusting manual settings for exposure. From there, there was very little I needed to adjust in the field, except when I was going for a specific effect.

In this way, I rarely thought about the camera as a tool in itself, just as an artist rarely thinks about the brush in their hands, except to change paints or switch to a different tip. Instead, I was thinking about light, about composition, about subject: I was thinking about the most important parts of photography. I wasn’t wondering what photometry mode I was in. I was simply looking through the lens and capturing moments.

Optical Viewfinder

Well, not quite. Or at least, not always. You might be used to a camera having the viewfinder in the middle of the body. Initially, this was done because inside the body of the camera was a series of mirrors that reflected the image coming into the lens (which is also in the center of the body) up and into the eyepiece, allowing a photographer to compose and focus based on what was coming through the lens.

But there’s another way: the rangefinder. This system uses two windows, where the photographer looks not through the lens, but through a viewfinder on the body. This is linked to whatever lens you have attached, showing an illuminated guide of the frame (framelines), and using another window elsewhere on the camera triangulates the distance between a subject, focusing as you align images inside the viewfinder.

This is an extremely effective means of focusing, and perhaps most interesting to me, because you’re not looking through a lens, you can see beyond a lens. You can see things before they come into your frame, or better see the things that lay outside your frame to help compose a shot.

Unlike the control paradigm, this was completely new to me. It was nothing short of a revelation. It never occurred to me you could make photos like this, and in combined use of the EVF and OVF (whose selection switch is deeply satisfying, I might add), it opened up a whole new possibility for my photography.

The optical viewfinder on the X-Pro3 is bright and beautiful. I haven't enjoyed a photo composing experience this much since looking through the ground glass on a Mamiya RZ67. And if you flip the switch on the front of the body, you get an excellent electronic viewfinder, which shows you a live feed from the sensor, so you'll know exactly what your image will look like—no guesswork involved.

But the X-Pro3 is only like a rangefinder; it isn’t actually one. There’s no second window to provide that triangulating function. Instead, it simply emulates this experience through some digital trickery.

If you’ve never used a rangefinder, you might not know what you’re missing. And Fujifilm gets close to emulating the feel of a rangefinder, and even provides some advancements, like a picture in picture display for checking focus, advanced parallax correction, etc. etc. The X-Pro3 and its lenses are often small like a rangefinder's, and being an electronic camera, it gets close to a lot of the other benefits rangefinders offer, like quieter (or silent) shutters, less camera shake, less internals period (i.e., potential failure points), and no “blackout” when you actually press the shutter to take an image.

So what’s the problem?

Half-Measures

Here’s where that rangefinder-style comes into play. I always found manual focusing very tricky on the X-Pro3. Worse, the problem is twofold. The body not being a real rangefinder forces you to work with things like focus peaking or emulated split-prism focusing to get focus if you dare slip it from AF mode. Additionally, despite the analog push, everything on the camera and lenses is electronic.

Basically every Fujifilm lens has an aperture ring, but like the camera is only rangefinder-like, this too is almost for show. If the lens is not attached to a body that’s turned on, moving the aperture ring does nothing. It just sends a signal to the camera to change the aperture. Even the focusing is electronic, what’s called “focus by wire.” This means the two barrels on the lens for aperture and focus are not directly tethered to any of the components in the lens.

This always gave manual focusing a “floaty” feel to me. It’s slightly laggy. It’s okay in most contexts, but for street photography, or something like photographing children, you’re probably going to have a bad time.

In a camera that felt designed to shrink the gap between action and result, these half-measures seemed to actually increase the distance, obfuscating critical functions in a way that felt bad.

So just use autofocus, right? That I did. My X-Pro3 was almost always in single-point focus, where I’d set a focus point, grab focus, and then recompose before taking a shot. The autofocus system is fine, but even at the time, a little outpaced by that of its competitors. Sony in particular had superior autofocus, and I missed a few shots from too-imprecise focus points, failure to eye-track, or something similar.

Additionally, I’d come from a Fujifilm X-H1, a hybrid photo/video camera, which notably had in-body sensor stabilization, allowing for sharp handheld shots at slow shutter speeds. Fujifilm left this out of the X-Pro3, saying they simply couldn’t fit the module for this function in the body of the camera. It’s understandable, but it never feels good to have a new camera miss features.

Beyond that, I never felt quite confident in low-light. I made a handful of images at night, but often felt the noise performance at the ISOs I wanted to shoot at was just not quite there. This is in part due to the smaller sensor size; there’s simply less area to gather light. I almost never felt limited by the APS-C sensor otherwise.

That is, except in editing. I don’t love editing photos, which is part of why I gravitated towards the Fujifilm film simulations; they allowed me to think about post-production less. But I still shot RAW in conjunction with JPGs, and occasionally upon loading an image into Capture One, I’d feel backed into a corner with the image, as if I couldn’t push the colors in a direction I wanted to go if it differed too much from the color science. Perhaps this was a personal failure, a lack of imagination, or a mismatch between photography and editing process, but the result remains.

If the promise was to be a minimal camera with better electronic support, Fujifilm could’ve gone farther to make this the reality.

Okay, so maybe the X-Pro3 is not a perfect camera.

Towards New Horizons

And yet. And yet! This is a camera with charm. This is a camera with heart. This is a camera with a sense of aesthetics! It felt like a breath of fresh air in a landscape of cameras all fighting each other to move ever closer to the middle. Even now, there are almost no cameras, no personal electronics period I’ve found that have excited me by the possibilities it offered in this way.

I was captivated by it from the first moment I saw the press release images, and that love affair lasted through the entire time I owned it, and as I made the difficult decision to let it go. I carried it with me almost every day for over five years, and as much as possible, kept it in my hands. It was my tireless companion from coffee shops and grocery runs, to international trips to Europe, Asia, and beyond. It was the camera I used when I made my primary living as a photographer, and I’ve made almost all of the photos I’m most proud of while looking through its viewfinder.

It’s often said no camera will make you a better photographer, but I push back against this. The X-Pro3 made me a better photographer, if by how much it compelled me to use it as much as anything else. It taught me to see in frames and think in terms of lenses, to search for beautiful light, to wait for the decisive moment, and to make photographs with intent for what you hope to capture, hope to convey.

But I’ve used it enough to see its limitations.

I lived in Chicago before I owned an X-Pro3, but my use of the camera is linked to my time there. I felt I had fully experienced the city, and fully experienced the camera. So it's time to move on; towards new horizons.

I’m out of Fujifilm for now, but I wouldn’t be surprised if I was back someday. Fujifilm might not have much to say about an X-Pro4 for now, but they're continuing to show how much they care through the new GFX100RF, and soon-to-be-announced X-Half (please call it something—anything—else).

Either way, the X-Pro3 will always hold a special place in my heart. I simply wouldn’t be the photographer I am today without it.

If you liked this post, but aren't yet subscribed to my newsletter, sign up below to get more posts like this delivered to your inbox. Members also get access to the exclusive bi-weekly newsletter, Refrakt, members-only posts, downloads, and more on the members page.

Paid members also get access to an exclusive members-only photography feed, and a one-of-one postcard delivered anywhere in the world.