Flat

Over time, I think most artists find patterns that seem to work for them. Often, when staring at the blank page, it can feel like you’re starting completely fresh, which is both the joy and the terror of writing. But photography is a bit different. So far, I haven’t yet encountered the moment where I felt like I needed or was forced to remake my process anew—but sometimes you hear something that shakes you up; makes you take a closer look.

I started using only prime lenses when I was in college. Beyond just the higher image quality they offer, the aesthetics called to me. Unlike a zoom lens, you’d never get caught between a standard focal length, photographing something at 32mm or something. It was simple—minimal—pure. Most of all, it felt artistic; forcing you to make decisions about the type of images you wanted to make, rather than hedging with a lens that could reasonably do almost anything.

Early on, I was limited mostly by budget, only able to afford a lens or two. Even as my means increased (meagerly!) I still found myself favoring specific lenses, specific focal lengths, though not always the same. I’d go through phases where I was married to the 35mm, the 23mm, the 18mm, and back to the 35mm again. It wasn’t uncommon for me to carry two lenses, but rare for me to switch, unless for a specific shot.

I even leaned into this at times: the idea of “one camera, one lens” extolled by groups of YouTube photographers, taken as a sort of a motto towards a system of aesthetic refinement. Photographers pushing towards this philosophy tend to mention names like Henri Cartier-Bresson (most famous for shooting 50mm, but not exclusively), and Vivian Maier (whose work was mostly made on an 80mm Rolleiflex TLR, but finding true adherents to the practice is difficult. Still, out of necessity or zeal I too operated under this worldview.

And then once and a while you hear something that throws a wrench in the works. I recently came across a video featuring Phil Penman, a street photographer known for his high-contrast black and white images of New York City (among others). “I never want to be shooting with just one lens,” he says, “because your work tends to look very flat.”

Huh, I thought.

Lately, I’ve been making images almost exclusively with the Minolta M-Rokkor 40mm f/2. I like this lens; a lot. After years of using wider focal lenses, it felt nice to go for something a bit tighter for a change. It’s a tiny lens, which makes it an ideal lens for daily carry. I like the rendering of the lens; sharp enough to make full use of the sensor, but generous, pleasing bokeh (even at a long minimum-focusing distance).

But was it making my images look flat?

I decided to go through my recent images, especially those made since moving to Tokyo, to find out:

First, perhaps it’s pertinent to determine what would make an image flat to begin with. One might say it is the opposite of an image with depth. Depth in photography is a fleeting spectre, perhaps the ghost all of us are chasing. It’s inherently impossible: photographs are flat. Still, through light, adjusting the focal plane, lens rendering, and other devilry, the illusion of depth can be conveyed. Further, I think flatness corresponds to a sense of sameness across images.

When I look back at some of the photos I’d made in the past, I feel as if I was trying too much. I leaned into extremely shallow depth of field; liberally applied grain to my images. But it was looking through the work of Ulysses Aoki that I came to appreciate what I came to think of as cleanness in an image. Aoki’s work spans a wide range, and he’s someone prone to experimentation, but a lot of that street photography of his I was drawn to doesn’t try to work too hard to convey meaning—it doesn’t need to. Instead, the image itself, unadorned, says everything it needs to.

This and the influence of other photographers changed my outlook, and hand in hand as my gear shifted, my images started to as well. As mentioned in my X-Pro3 review, a camera can influence the type of images you make, same as your vocabulary can shift the way you think. When I came back to using true rangefinders, the images followed. In a rangefinder, using manual focus, it’s common to make images not at f/1.4, but at f/4, f/5.6, f/8. This lengthens the depth of field, meaning more of your image is in focus, and can minimize some of the more particular characteristics of any given lens, especially when focused more than a few feet away. In doing so, a more neutral look might be achieved.

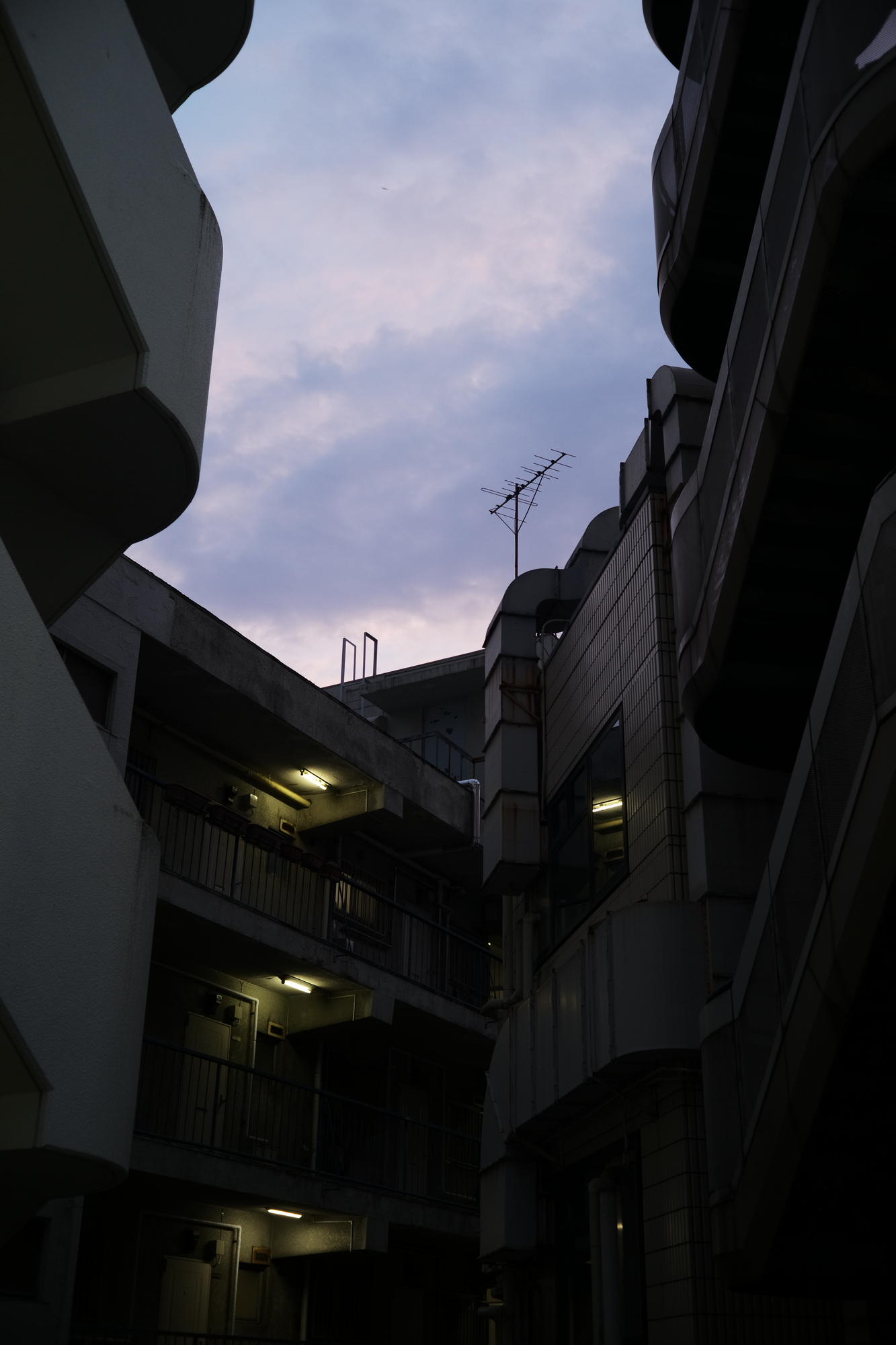

Beyond the characteristics of a lens, each focal length responds in a different way. And here, I start to see some uniformity. Take a look at these images:

Yes, this consistency is furthered by a similar handling in post-processing, but to me, I can tell they were made using the same lens.

Yet other images seem to buck this trend. At greater or closer distances particularly, the scene opens or closes, allowing a wider range of representations to be available. Take these images, for example:

None of this is inherently good or bad. Perhaps one could wave away the concept as simply a matter of style—which I don’t hear discussed in photography as much as some other mediums, but perhaps that’s a topic for another day.

More than anything, I want to resist stagnancy in my photography. I’m a habitual creature, at times prone to getting stuck in ruts as much as I am to finding a groove. Still, I’ve been very happy with the photography I’ve been making lately; maybe there’s no need to change a good thing. I’m going to continue using the 40mm. But maybe I’ll stick a 28mm in my bag as well.

Do you try to be consistent with your work, or are you always evolving? What do you do to try and avoid ruts? I'd love to hear it. Members can leave a comment on the site.