Is Street Photography Legal In the United States?

Street photography is one of, if not the oldest genres of photography. For over a hundred years, photographers have roamed city streets, looking for authentic moments to capture and share, highlighting something often less distorted than traditionally constructed scenes. Somehow street photography returned to the limelight in the wake of Instagram and YouTube photography communities, and this is probably where I first became acquainted with it. Yet for a practice that’s over a hundred years old, people still bristle at times about the prospect of yes, taking photos of people without their express permission. (I wrote an article about the backlash Tatsuo Suzuki, a Japanese street photographer, faced after appearing in a promotional video for a Fujifilm camera.) After describing the kinds of photos I make, I still have people ask me, “But do you ask people’s permission to take their photo? Is that legal?”

I wanted to write a bit about the practice, what the legality is, and why whether it’s legal or not is perhaps the wrong way to think about it.

Is Street Photography Legal In the United States?

Yes, street photography is legal in the United States. If you’re in Chicago (like me!), New York, LA, or anywhere in between, there’s no laws preventing you from grabbing your camera and going out to make some photographs.

The term I’ve often heard is “reasonable expectation of privacy.” That is to say, if you’re in a public space in the US (such as a city street, a park, or sitting outside of a café, as a few examples) these are all spaces you wouldn’t reasonably expect to be private. As such, any time you’re in such an area, you’re able to be photographed without violating any part of the law. And guess what? You probably are! From the security cameras on the sides of buildings or in lobbies, to the video calls and photos of passerby, and the cameras everyone seems to affix to their front door now, it’s becoming more and more likely that when you’re outside, you’re being filmed somewhere. Even so, I’ve never seen someone yell at a Ring camera or someone taking a Facetime call on a park bench, but I have been yelled at by strangers while out making photographs (sometimes by people I didn’t even photograph!)

The simple reality is that a lot of the other means I’ve mentioned are seen as less conspicuous than someone with even a mirrorless camera taking photographs, so you’re going to stand out more. While the negative interactions I’ve had are few and far between, and far outnumbered by the positive interactions, for anyone who’s tried street photography, you’re probably going to draw someone’s ire.

Beyond all that, there are a number of considerations I think are not only pertinent to street photography, but essential to consider for anyone thinking about taking up the practice. Namely, the ethics of photography, and street photography at large.

The Ethics of Street Photography

Something foundational to my own understanding of photography in general, not just street photography, is the idea that all photography is exploitative. This may seem harsh, or untrue. You may wonder how someone could “exploit” a mountain in a landscape photo. But I think of “exploiting” here in the least loaded sense: trying to best utilize or leverage the scene and tools and light and everything that goes into making a photograph into making the best photograph possible. Maybe you’re waiting for the light from daybreak to hit the top of the mountain peak, and using a long lens to isolate the mountain from its surroundings.

Of course, this becomes more complicated (and more loaded, tbh) when talking about photographing people. At the end of the day, as a street photographer, you’re mostly trying to leverage other people as subjects in the process of making art. As such, I think you have at bare minimum a responsibility to treat those around you (and especially the people you’re photographing) with respect, humility, and empathy.

For me, when I started doing this work a bit more seriously, I spent a lot of time thinking about my own personal ethics and intent with my work. What was it I was trying to accomplish? What did I want to capture, and what did I not want to capture? This has evolved over time, of course, and exists more as a series of personal guidelines, rather than hard-and-fast rules. I almost never photograph a child in a way in which they’re recognizable. I don’t photograph unhoused people, or anyone with the intent to other them.

I think that’s really the key point. I want to connect people. I want people to see my photographs, and be able to better see an insightful or funny moment that might’ve gone unnoticed. (My girlfriend often asks me what I’m chuckling at when we’re out, but to me, daily life is filled with coincidental and humorous moments.) I want people to see my subjects, and try and think about what that person might be thinking, seeing, feeling. I want people to see my photographs and simply gain a better recognition and appreciation for beautiful light around us.

This is something I’d recommend doing before you take any photos, and also during. I’m not talking about going crazy about limiting yourself, but every once and a while when I’m out making photos, I like to think to myself, what am I trying to say with this photograph? What do you want to capture? Is there anything you don’t want to capture?

Getting Yelled At

That said, if you’re making street photos for any serious length of time, you’re probably going to encounter someone who’s less than pleased. Even so, this is not something I would obsess over. Despite the ever-presence of image capture, despite the legality, there are people who don’t want to be photographed. There are going to be people who don’t even want to see you taking photographs, even if it’s not of them. There is some level of confidence required in this genre. (If you'd like to start, but the idea of moving quickly around a city makes you nervous, consider trying to "work a scene"; I wrote a guide on the method here!)

Yet what I bristle at are newer photographers asking what the laws are, how to interact with police, or how to take photos in an undetected way. The excellent Street Photographer’s Manual by David Gibson says, “If you get stopped taking photographs, you’re doing something wrong.” (That is a bit too extreme, but you get the point.)

Sure enough, I probably wouldn’t recommend bringing your Canon 1DX and 500mm lens out downtown (...though that’d probably make some unique photographs!) But I think there’s sort of a mirror principle at work. The more you try and hide yourself, the shadier you appear… the shadier people will think you are. Just raise the camera to your eye; as long as you’re working with a good intent, and trying to treat those around you with empathy and respect, you’re not doing anything wrong.

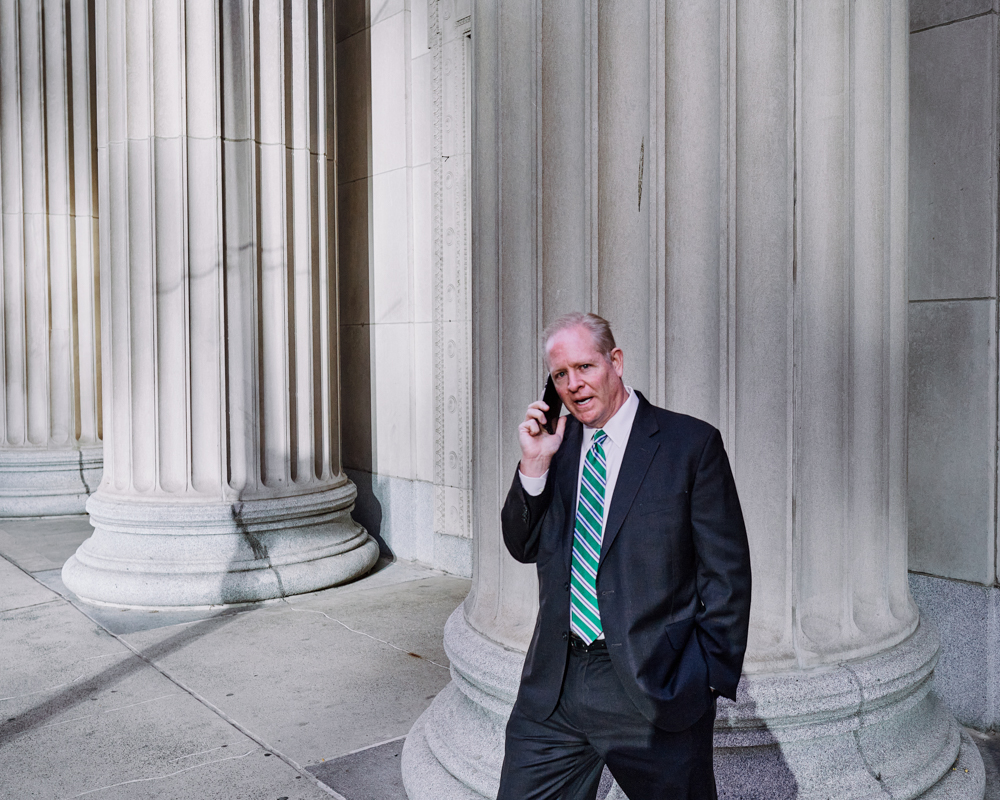

Here’s a photograph I took a couple of years ago.

When I saw this man, he was half-obscured by the repeating columns in a way I thought was interesting. Unfortunately, he broke the illusion, as he stepped out to yell at me once he saw me start to make this image. (This was several years ago, and I haven’t had a negative interaction since.) He was unhappy, and I couldn’t even really figure out why. I simply kept walking, stayed calm, spoke earnestly, and in spite of him following me for several blocks, it never escalated beyond that.

It was unfortunate he felt so aggrieved by what I’d done. But I was simply trying to take a photo. I wasn’t trying to hurt his feelings, or make him feel flustered. I never want to photograph someone having a terrible day, really. I don’t know what his deal was, but simply trying to de-escalate, continuing to move away, and not panicking or becoming aggressive in return has always served me best.

Why Not Just Ask Someone if You Can Take Their Photo?

If the issue often lies in whether or not people are okay with being photographed while they’re in public, why not simply ask if you can take someone’s picture? You can; it’s just when you do, it becomes street portraiture. Whatever expression or candid moment they were a part of is instantly shattered, instead becoming something performed. There’s nothing wrong with these photos, or even in interacting with a subject, like Werner Herzog or Bruce Gilden does. It just becomes something different from what I’m personally trying to capture.

For me, the photos I’m proud of were worth the small risk that someone would become upset.

Street Photography As A Connecting Thread

Finally, I’d like to talk more about my view of street or candid photography, as a way to connect people. I mentioned above that I’d like my street photography to make people more aware of the people, moments, and light around them. But it goes even further than this. I think the photos themselves can connect people, both viewer and subject, and subject and photographer.

While I try not to disturb a scene before I capture it, I’ve had tons of really pleasant interactions with a subject after I make a photo. I think lowering the camera and smiling at someone goes a long way towards making them feel comfortable, and conveying your intent. Here’s an older photograph of mine that I still love:

The woman rests her hands on a cardboard box she’s put on top of a stone barricade. The box implies an ending, to me. But the silly, almost childish balloons behind her give a cheerier impression. After I took this photo, I chatted with her a bit, and learned it was her last day at her job; certainly a bittersweet sort of moment.

Are these sorts of interactions impossible without a camera? No, but they’re aided by one. And more so, they allow me to share these moments with others, maybe making even a non-photographer more likely to notice the beautiful moments happening around us all the time. But before you can capture them, you’ve got to be able to notice them yourself.